If you are somewhat like me, than you want to know as much as possible before making important choices. And career choices clearly belong in this category.

Unfortunately, career paths (and life in general) are more like navigating through dense fog. No matter how hard you try, from where you stand you can only look that far. And even worse than that: There is no map you can consult. The world is constantly changing and everyone has a different starting point, different liking, preferences, priorities, skills, means, contacts, etc. You hence have to sketch your own map!

Anyone that makes conscious career choices has most likely one in his head already. If I would have drawn my own career map 5 years ago, it probably would have look like this:

This would have been my career path map about 5 years ago. How would yours look like? Illustration by Florian Huber, can be reused under the CC BY license.

My aim at that time was to stay in academia, eventually ending up on one of the few permanent positions such as tenured group leader or professor. In most countries, the academic system has an insanely high ratio between temporary and permanent positions. The vast majority of people doing the actual research, but also a large amount of the university teaching and mentoring are on temporary contracts (PhD students, postdocs, junior group leaders). The sparsity of permanent positions is creating a lot of competition and has the consequence that most researchers doing a PhD or postdoc won’t be able to get a permanent position in academic research. And many of those who do get a permanent position often have to accept quite some compromises along the way (accepting several non-permanent positions at different places/countries with very little planning certainty). No wonder that many people in academia suffer from unclear career perspectives.

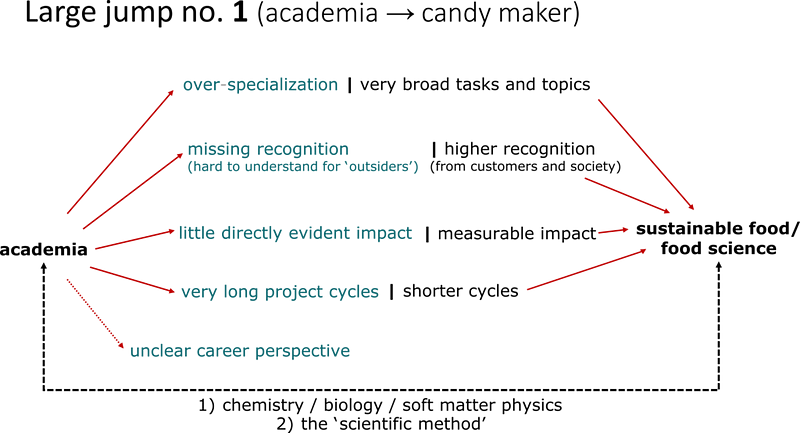

While the missing planning certainty sparked first doubts about my career goal, it — funny enough — was no main factor for leaving academia in the end! The main reasons I decided to not continue my paths in academia were

- Over-specialization:

Over the course of my postdoc I realized that I was increasingly bored at poster sessions (before I had always enjoyed them a lot). I was loosing interest in the details of the research done in my field and only continued to care about the “bigger picture”, the keynotes. Actual academic research, however, is to a large extend about the details.

The idea of becoming a permanent researcher in the field I was in, started to appear more and more discouraging. Imagining myself still working in the same field over 30 years, meeting the same small circle of people,[1]visit the same conferences, made it clear to me that this was not what I wanted. - Missing recognition:

Once you make it to the top within the academic systems, this “problem” might disappear. Established professors and group leaders usually do get quite some recognition for their work. Recognition for the work of everybody working for them (students, PhDs, postdocs) also counts as recognition for them, which in a way acts as a multiplier.

But for many PhDs and postdocs, fundamental research means that they work on extremely difficult and complex tasks. It often takes several years before their work produces important results. What makes things worse is that due to the high degree of specialization (see (1)), often even those important results are only important for a very small field. This sometimes gave me the feeling that only a very small number of people in the world would really appreciate my work. In addition, I found it very difficult to share personal successes with people out-of-the-field, and even more difficult with people out-of-science. - Missing (or hard to sense)impact:

This is largely a psychological point. Because I DO strongly believe that fundamental research is very valuable and is of greatest importance to society!

However, for those doing this fundamental research it often doesn’t feel that way. If you count your own personal scientific contributions and ask yourself how the world would be without them, the answer often would be “not so different”.

Let me again stress that this is a lot about perception. Science is an incredibly complex, collective endeavor. It has very little do to with the romantic narrative of thescientific genius who single-handedly disrupts entire fields of.[2] Still, it can feel frustrating at times.

While my doubts concerning a career in academia were growing, I had developed an outgrown hobby and passion. This was food science, chocolate, and anything candy. This included reading and writing about chocolate and candy making, about food politics and issues with food production. I had started to develop my own recipes for plant-based alternatives to candy products that otherwise would contain a lot of dairy products. And I became increasingly aware of the drastic impact of our current agriculture system on our environment and on climate change.

When I finally came to the conclusion to quit my academic path, I realized that working in food might solve the issues I mentioned above. With animal agriculture being responsible for about 80% of the greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture,[3] but also the heavy use of resources such as land and water, I felt that by being committed to develop novel, high-quality, plant-based products, I could really have an impact (small, but visible).

I was also heavily attracted by the broad range of aspects such a business would touch upon. From creative product development tasks, to social, political, environmental aspects. And not to forget, there was a clear science aspect as well! When I was working on my new recipes at home, such as for making vegan caramels, I wasn’t thinking so much in terms of classical recipes. I realized I was approaching things more as a soft matter physicist. How to get the necessary amount of Maillard reactions to produce the complex, rich aromas? How to get the free water content for shelf life? How to get the right emulsion composition for the desired mouth feel and texture?

It took me about 2 years to prepare. I took professional chocolatier courses where I always was the only academic among pâtissiers, chefs, and bakers (which was really a lot of fun!). I developed my first set of products, talked to many people, drafted a business plan, inquired necessary professional equipment and regulations.

And when in 2015, I accidentally came across a well-suited location I felt that I had reached the point to say “Now, or never”.[4]

Illustration by Florian Huber, can be reused under the CC BY license.

Illustration by Florian Huber, can be reused under the CC BY license.I went for “Now” and rented the place. I officially founded my company KÄNDI right after that and started to transform the place to a professional culinary workshop. In parallel I prepared and ran a crowdfunding campaign to get extra initial funds, but mostly to get first exposure and customers. For the first months I still kept a 50% position as a postdoc, but soon realized that I couldn’t do both things at the same time. My mind was constantly busy with my new entrepreneurial adventure, so from 2016 on I started working full time for KÄNDI.

Be aware: I was still a faaaaaaar way from a full time salary there. Actually in the beginning I was still far from any salary at all. Because of this, but also many other things, my new life as an entrepreneur was quite a roller coaster. But I learnt a lot of great things. And I developed, designed, and produced some very special candy products that I was extremely proud of. It felt great to look at a full rack of handmade candy bars, chocolates and caramels at the end of a productive week. And it felt great that I knew they were all made from highest quality ingredients (organic, fair[5], fine flavored ), and that the recipes were my own and entirely plant-based.

Unfortunately, being proud of my product wasn’t enough. Even the enthusiastic responses from my customers were not enough. It turned out that my business model did not work the way I wanted, and not the way I needed to continue. And worse than that: I did not see a clear perspective of my business model work out somewhere soon.

( → see also my previous lessons learnt blog post)

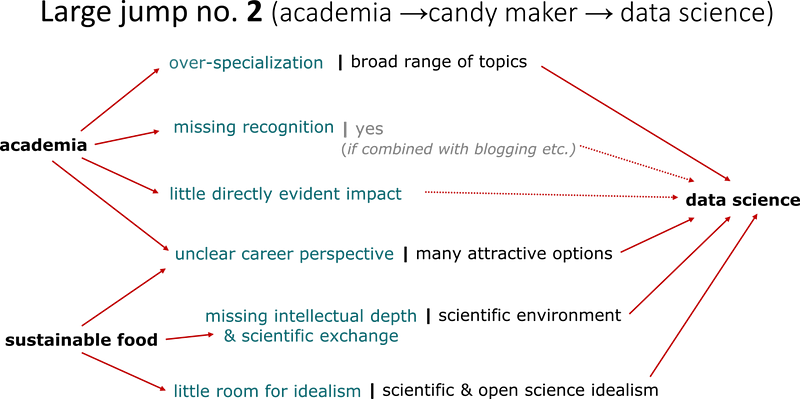

This was putting me under a load of pressure, including financially. Still, in the end it was not only about the money. Equally important (if not more) were other factors that made me realize that I should not continue with KÄNDI. The division of tasks turned out to be very different from what I had expected and hoped for. While I was prepared to spend time and money on sales and marketing, I was not prepared that selling a food product would be MORE about marketing than about the product. This was not enough accounted for by my business model. And more importantly this was not how I wanted to make business.[6] It also meant that I had not enough time for the things I cared about most: product and concept development, training, workshops, and actual production.

Closely related to that, I would say that there was far too little room for idealism in the food business field I was in. I am not saying that there are no idealistic entrepreneurs at all, luckily I did meet a few that were able to combine high idealistic standards and business success. But it is very hard to find the right niche that does not ask to many compromises. Far too often I had to realize that it was only coming down to price and margins in the end. And the food market is extremely competitive.

It hence became clear to me that I had to stop. Which was a very difficult decision to make. Next to working for KÄNDI I had not developed any plan B, so it took me a while to re-orient and decide on a new direction and on new goals.

After many months of networking, talking to people in different areas, look at job offers, applying for jobs, working myself into new fields… I found that the (broad) field of data science appeared to be a very good match.

Most of all, data science promised to be a field that would bring many more tasks related to quantitative science, including complex statistics, abstract thinking, data analytics etc. Because even if I had very consciously left academia, it was not because I did not like science! My former decision was rather against being a single-domain specialist.

Having worked far away from academia actually made some of the main advantages of working in science stand out even more. No matter how much people INSIDE academia complain about the flaws of the academic system (there are plenty!), compared to a corporate setting I felt that academia leaves much more room for idealism (collaborations and exchange of ideas are common practice, and there is very little pressure from ‘the market’). Compared to most corporate settings scientists also have a lot more freedom to explore ideas outside short-term goal-oriented settings.

Illustration by Florian Huber, can be reused under the CC BY license.

Illustration by Florian Huber, can be reused under the CC BY license.In September 2018 I started working as a data scientist and research software engineer at the Netherlands eScience Center. This suddenly brought me back into the world of academic research. This time, however, I would not work in one highly specialized sub-sub-field! At the eScience Center we have more than 50 researchers from many different disciplines and backgrounds working together on a wide range of scientific project. To me, the most incredible thing about the center is that it is an extreme incubator for interdisciplinary work and cross-disciplinary method and knowledge transfer. Extreme, because the level of interdisciplinarity is much higher than in any academic setting I have been to. Here, you can work on projects ranging from digital humanities to astrophysics which in classical academic settings is next to impossible.[7]

Back to the beginning. Back to the map metaphor.

Let’s come back to the picture of navigating through fog without an all-knowing map at hand. Speaking in this picture I would draw a few conclusions from my own experiences on career paths exploration.[8]

Naturally you should take all those opinions and advices with a grain of salt. What some consider a perfect job or working environment, might totally not fit your interests, skills, or personality.

- Don’t be too persistent.

Safe career paths are fine. But try to be a bit exploratory. At the very least in form of Gedankenexperiments: Try to imagine how it would be to go left or right. Talk to people out of your own field (see above). It’s fine if you stick to your initial career plan, but knowing some alternatives will give a greater sense of having done so consciously, and not simply because every step you did was simply the most logical one to follow up on.

I have talked to quite a few people that had reached their career goals only to realize that it was actually not what they really enjoyed doing… - Make sure you develop.

Next to knowing what career path to follow or not, I think it’s important to avoid getting trapped in too much routine tasks and repetition. When ending in a situation where you feel you are not acquiring new skills, force yourself to take a step back and look at your situation to see what you could change to include learning new things into your routine. Or maybe that is indeed the right moment to move on?

You might think that in academia such things rarely happen, but I have seen exactly this thing happening a lot. As a PhD student or postdoc it can easily happen that you become overly focus on some narrow, far-away goals. This one measurement that needs to work, that one equation that need to be solved, that one paper you need to get published. In the end there can be long periods where people do virtually nothing else than “measure something” day and night for years, ignoring everything happening left and right of them, only focusing on this one future goal. While some perseverance is indeed sometimes needed to achieve important goals, it should still be questioned frequently. I think it too often leads to a feeling of “I now have no time for this” towards anything that doesn’t entirely fit this one single final-distance goal. But in my experience it often turns out to be a poor choice of priorities. Not only might this one final goal be further away than though or not be that desirable after all. It is also the sum of all those small skills that you could have picked up along the way that might make all the difference in the future.

An example from my experience: During my time as a postdoc we had an initiative at the institute to switch from proprietary software (MATLAB) to open-source solutions (python). Surprisingly many PhD students and postdocs considered this a distraction, taking away their precious time to do research and write papers. But if you look at it from some distance that’s a rather poor argument, because you spend an extra few weeks which is near to nothing compared to the 4–5 years it takes to get a PhD. In my case this small sidetrack was clearly more than worth it. It was one of the key skills that made it possible for me to enter the career of a data scientist at all (outside academia, most people do not count MATLAB as a real programming language, certainly not a relevant one…)!

But now: onto your own map!

In the end all advice I give here is only based on my own limited experience. Tales from exploring my own career map. Yours will look different.

In the end, that’s what it makes things so difficult: No one that can tell you how to navigate on your own career map (or in life in general). So best make your own choices and explore your own map. Only you can do that, so be as adventurous as you can effort to be and enjoy your very own journey of discovery!

Any further questions for me? Any advice you’d like to give or share? Any opinion on this blog post? Then please let me know!

This blog post is based on a presentation on I gave at the Marie-Curie Alumni Association annual conference in Vienna (Feb 2019). See slides on zenodo.

[1] Not that I had any problems with the people in my field. I have met a lot of great people in my former field during my time as PhD student and postdoc. But I found it weird to imagine keeping such a very small circle of people as my peers for the next 30 years or so (on the group leader and professor level I found there was very little fluctuation, and very little cross-discipline movement).

[2] See the very readable book “The Age of Wonder: How the Romantic Generation Discovered the Beauty and Terror of Science” by Richard Holmes

[3] See UN FAO 2006 report.

[4] In retrospect I shouldn’t have felt that urge, see my other blog post on the lessons I learned.

[5] And not only fair in the sense of the fair trade label, but truly fair. For instance did I work with a very special chocolate from a great Ecuadorian chocolate company. They not only get their beans from local cooperatives, but also produce the chocolate in the country of origin. This is still a rare exception in the world of chocolate. Thanks HojaVerde!

[6] If you take marketing, sales, and packaging together it is not rare to see small companies spending 70–80% on marketing and sales, and only 10–20% on the actual product!

[7] In my personal case, I do not work on that large range. But my current projects give me the chance to work in very different scientific fields as well. Including metabolomics, genetics, psychiatry/behavioral and social sciences, and others.

[8] Obviously, and the same is true for all of the above, it doesn’t hurt to acknowledge that worrying about “career choices” is a luxury problem. As it suggests that one is in the luxurious position to be able to consciously decide to some extent about the own professional path. Many people are not that lucky.

Originally published at http://everydayadatapoint.com on April 26, 2019. Copied with permission by F. Huber